Global and national changes in the operating environment are forcing companies to expand their support functions. This delivers value to third parties but is not reflected in the better prices of products and services or increasing operating profit as part of the added value generated by the companies.

Labor productivity has grown very slowly in Finland in the 2000s. This seems surprising considering that the application and use of digital technologies in businesses has made rapid progress at the same time, and this has been expected to spur great leaps in labor productivity in all sectors.

This phenomenon of slow labor productivity growth, known as the productivity paradox, has been studied a great deal in economics and industrial engineering, and a number of alternative explanation models have been put forth. So far, however, none of the alternative explanations provide a completely satisfactory answer as to why labor productivity is not improving. Could the explanation be found in the diversity and complexity of the operating environment of companies and organizations and the resulting significant increase in the labor input required by support functions? This is the question we will reflect on in this text.

Productivity growth and the resulting economic growth are directly linked to the wellbeing of Finnish citizens. Labor productivity usually refers to the added value produced by companies divided by the number of labor hours used for its production.

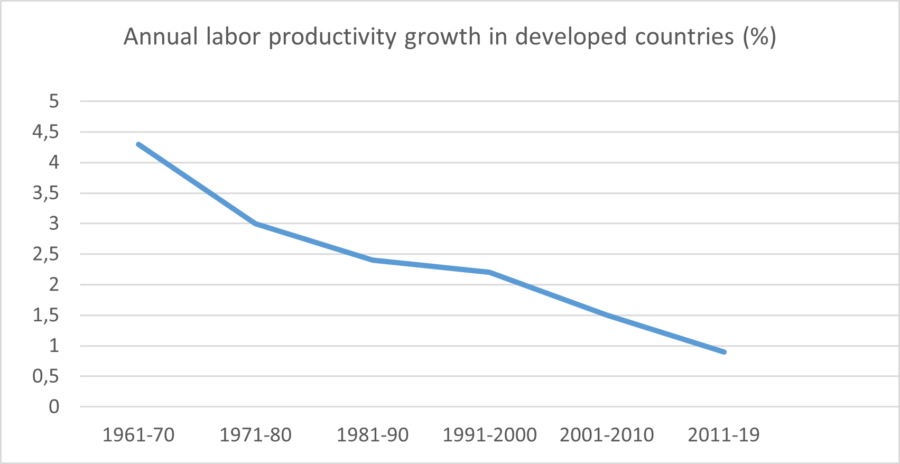

Figure 1 below shows the growth in labor productivity in advanced economies in the US, Canada, Japan, and Europe. Labor productivity grew in these economies by an average of just over 4% a year in the 1960s, fell to 2–3% in the following decades, and declined further to a level of 1–2% in the early 2000s, where it has steadfastly remained. The trend is therefore declining, as shown in Figure 1 below.

In Finland, productivity development has been similar to that of other advanced economies, although the years of Nokia’s spectacular rise in the 1990s are reflected as specific national characteristics in the figures. Labor productivity grew by 3 percent a year in the 1960s, slowing down to 2.5 percent in the 1970s and 2 percent in the 1980s.

The following decade saw a rise in the annual productivity growth rate to 3.7 percent, driven by Nokia, but this subsequently fell to 0.8 percent in the 2000s, and by 2010–15, the annual trend was negative, -0.9 percent.

What can explain such poor labor productivity development, especially since we should have access to all possible digital technologies in the 21st century to improve productivity?

Are we using digital technologies just because others are using them? To return to the Nokia era, it is worth noting that even during the growth in labor productivity driven by Nokia, we were able to reduce the degree of automation in our production lines and business processes.

Practically all businesses and various economic operators also have access to computers, the Internet, e-mail, cloud services, and increasingly fast and reliable communications. In addition, the past decade has seen the introduction of the Internet of Things, Industry 4.0, and most recently, statistical learning classified as artificial intelligence, into the toolbox of digital technologies available.

Technology companies and consultancy firms were quick to promise an annual increase in labor productivity of one or even two percent, provided that the latest digital technology fad was adopted. So why is the labor productivity trend now negative?

Researchers have found several alternative explanation models for weak productivity growth. Pohjola (2020) divides the suggested explanations into four main groups: 1) measurement errors, 2) delay in the productivity improvement created by digitalization, 3) decline in technological and scientific progress, and 4) slowing of the spread of innovations compared to previous decades. So far, no explanation model has received wide acceptance among researchers.

According to studies, measurement errors would affect the service sector, especially digitally produced services, where productivity is more difficult to measure than in manufacturing. Many researchers have disputed this explanation in their studies, although they acknowledge a degree of inaccuracy in the measurements.

The delay in the application and deployment of digital technologies assumes that it takes years for businesses and organizations to learn how to exploit new technologies. This is certainly partly true, but what undermines the theory is that even the extensive digital technology investments made 10 to 20 years ago are not reflected in productivity.

The third explanation, the decline in technological and scientific progress, does not seem very plausible either, given the recent advances in digital technologies. At least it does not adequately explain the slowdown in productivity growth.

The fourth explanation, the slowing spread of innovations compared to previous decades, seems downright implausible, as new digital technology innovations and fads spread throughout the interconnected world in a matter of months.

In addition to the four explanations identified by Pohjola (2020) above, there is a fifth explanation. This can be derived from the notion put forward by Nicolas Carr (2003) that technology available to all companies does not increase anyone’s productivity, since competition transfers the advantage, i.e. the added value, to customers as lower prices. The productivity gains achieved therefore go to the customer, but are not reflected in the company’s productivity or, correspondingly, in GDP.

It should be noted that no commonly accepted explanation as to why productivity growth is slowing down despite the adoption of advanced IT and automation has been found. There is good reason to talk about the productivity paradox.

If we compare the business environment of the 1960s and today, we can safely say that the current environment is much more complex and diverse. Diversity arises particularly from the demands and pressures of global markets and regulation, as well as those posed by society, such as sustainable development. As markets and society evolve, companies and organizations operating in them are also increasingly required to perform activities that are not directly related to the company’s core activities.

Marketing, contract law, environmental and sustainability considerations, developing employees’ skills and maintaining their work ability, and managing the company image all require the company’s attention and often more resources. Addressing these issues is naturally part of a broader positive development that has taken place in Finland and other developed countries since the 1960s. We benefit from this development both as customers, employees, and citizens in a variety of ways.

From the perspective of a company or organization, however, its non-core activities, such as compliance, contract law, HR management, marketing, quality and environmental management, and other similar functions, absorb resources but do not increase the value of the products and services it produces, nor the added value it generates. A simplified example is presented below.

Let us imagine a metals company called Acme Corporation, which manufactures 100,000 components a year and sells them to its client Big-Acme Corporation. In the 1960s, a total of 95 of Acme Corporation’s 100 employees were manufacturing parts using lathes and presses, while the CEO, CFO, payroll clerk, HR manager, and secretary took care of administrative matters. In 2020, the company only employs 25 metalworkers in the factory, but thanks to digital technologies and automation, they continue to produce 100,000 parts a year. For simplicity, let us assume that the price of components and other factors have remained the same. This means that labor productivity has almost quadrupled in production!

Now, however, Acme Corporation has customers all over the world. Global compliance is therefore managed by a team of ten instead of the CEO alone. International operations have also required the recruitment of three contract lawyers. HR management, too, now employs a number of specialists responsible for compliance with labor law and labor agreements, as well as responding to the needs of the personnel. A social media specialist in charge of the company’s public image responds to the concerns and complaints of citizens and various organizations practically in real time. An environmental manager and team are responsible for compliance with environmental regulations and addressing the concerns of environmental organizations. A designated corporate responsibility coordinator has also been hired. Consequently, there are now 25 administrative employees instead of the previous five, which means that the added value per labor hour has not quadrupled but doubled since the 1960s.

Case Acme Corporation is a good example of how growing government-imposed regulation, market requirements, and pressure from society at large is forcing companies to use their resources to meet the new requirements. A variety of support functions have emerged alongside the company’s core functions. Support activities provide a wide range of direct and indirect benefits to the company’s stakeholders, customers, employees, and society, but for the company itself, the benefits may not be reflected in the higher value of products and services but mainly as increasing costs.

Original article Kanava magazine, no. 2/2021, pp. 34–36, March 5, 2021. Kanava is an opinion magazine for social issues.

SOURCES:

Carr, N., (2003), IT Doesn’t Matter, Harvard Business Review, May, pages 5–12

Pohjola, M., (2020), Teknologia, investoinnit, rakennemuutos ja tuottavuus – Suomi kansainvälisessä vertailussa (Technology, investments, structural change and productivity – Finland in international comparison), Publications of the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment 2020:5